Even though China’s decision to grow its nuclear weapons stockpile isn’t primarily directed at India, it nonetheless has inexorable consequences.

Nuclear test near Las Vegas, Nevada, in 1962. The US still enjoys a giant lead in terms of the size of its strategic weapons stockpile, the means to deliver them, and the technological means to defend itself against nuclear attack. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

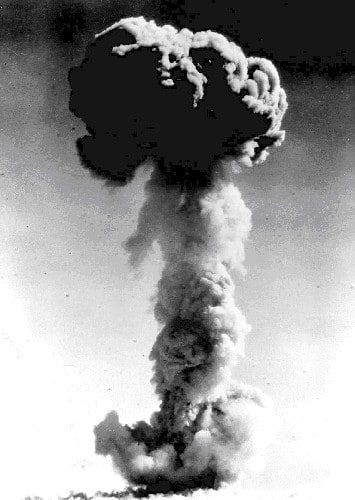

Less than a fortnight before a great mushroom cloud rose over the Lop Nor lake, a small group of analysts at the United States Defense Department issued a grim assessment of what China’s imminent test of a nuclear weapon would mean. “China is determined to gain status as a world power, primarily by reducing US power and influence in Asia and the Western Pacific,” they asserted. By 1980, Chinese nuclear capability should reach the point “where it will be necessary to think in terms of a possible 100 million U.S. deaths whenever a serious conflict with China threatens”.

Chinese nuclear bomb - H639-23 (Photo: Max Smith via Wikimedia Commons)

Chinese nuclear bomb - H639-23 (Photo: Max Smith via Wikimedia Commons)

For some years now, concerns have been mounting about China’s nuclear arsenal. Earlier this month, the Pentagon warned that Beijing planned to expand its stockpile of warheads to 1,000 warheads, up from an estimated 300-400 today. In addition, China has fielded the DF17 hypersonic glide vehicle, designed to evade US anti-ballistic missile defences, taken measures to help its own missiles survive an American nuclear strike, and is working on building a new long-range bomber with stealth features, the H20.

There’s little doubt China’s build-up is driven principally by its competition with the US: the world’s principal superpower still enjoys a giant lead in terms of the size of its strategic weapons stockpile, the means to deliver them, and the technological means to defend itself against nuclear attack. This massive asymmetry, Beijing seems no longer willing to countenance.

Even though China’s decision to grow its nuclear weapons stockpile isn’t primarily directed at India, it nonetheless has inexorable consequences. China’s capacity to deliver a first strike that can annihilate a significant portion of India’s own nuclear weapons before they are launched poses an obvious threat. New Delhi has already begun growing its arsenal, as has Islamabad; most experts believe both countries will have some 250 warheads by the end of the decade.

Finding an appropriate response that doesn’t lock India into an nuclear arms race, draining precious military resources, isn’t easy. How large does India’s arsenal actually need to be to ensure the credibility of its nuclear deterrent posture? And what delivery systems and defensive technologies ought New Delhi focus on acquiring to address the new threat?

Like with so many strategic issues, part of the answer lies in a clear-eyed appraisal of the character of the threat. Fear shapes irrational responses, United States State Department experts warned in an October 16, 1964, memo, written on the same day that China’s secret Project 559 tested the country’s first nuclear device at Lop Nor. Even though China’s nuclear weapons would allow it to “pose a nuclear threat to US bases in Asia and to use nuclear weapons as an umbrella for covert non-nuclear operations and for support of insurgency”, the experts believed that that was not the whole story.

The US State Department experts argued, that “the great asymmetry in ChiCom (Chinese communist) and US nuclear capabilities and vulnerabilities makes ChiCom first use of nuclear weapons highly unlikely against Asian nations”. As important, China’s acquisition of nuclear technology did not, in itself, alter “the real relations of military power in East Asia”.

In other words, the US State Department experts concluded, “the basic military problems we will face are likely to be much like those we face now: military probing operations designed to test the level of the US commitment and response; relatively low-level border wars; ‘revolutionary’ wars supported by the ChiComs; and pressure to keep US nuclear weapons from the area”.

The strategic circumstances India now faces are different—China is, after all, an emerging economic and military superpower, not a desperately poor and insecure post-revolutionary state—but the question isn’t. India’s responses will have to carefully judge what kinds of geopolitical outcomes China seeks on its western borders, and what kinds of wars are therefore probable.

Even given the asymmetries in the nuclear capabilities of Beijing and New Delhi, it is impossible for People’s Liberation Army planners to be certain no Indian nuclear weapons would hit its cities in a future nuclear war. Thus, Beijing would only risk a conflict that crossed India’s nuclear red lines—like the loss of significant territory, or the obliteration of national sovereignty—if the gains outweighed the potential cost of losing large population and economic centres. New Delhi faces similar constraints.

There is no algorithm that allows planners exactly what the decision-making calculus of such a conflict might be, or what circumstances might bring it about. No military planning, however, can anticipate and prepare for every possible kind of war; New Delhi, therefore, needs to develop a lucid and granular understanding of what kinds of conflict it thinks are probable.

A second layer of thinking about the nuclear threat posed by China has to do with time-frames. Experts Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda, among others, have noted that the Pentagon’s estimate that China will have have 1,000 warheads by 2030 is an assessment of capability, not currently verifiable intentions. The assessment rests, Kirstensen and Korda have argued, on the construction of missile silos—some numbers of which may be decoys, intended to confuse US targeting during a first strike—and estimates of how much plutonium China could produce. There’s a difference, though, between capability and intentions.

Indeed, some experts believe China’s modernisation of its nuclear arsenal—like its programme to build Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicle, or single missiles carrying several nuclear warheads, or its hypersonic missile programme—is primarily aimed at counteracting the growth of US anti-missile defences, and its offensive forces. Even if China could be sure a significant proportion of its 350-odd missiles would hit their targets, the argument goes, it could be certain the US would not initiate a full-blown war.

New Delhi, similarly, needs certainty that its nuclear deterrent can absorb a Chinese first strike aimed at destroying its assets and command centres—and then deliver assured retaliation. This end may be better served by more sophisticated means of delivery—like expanding the numbers of warheads on ballistic-missile nuclear submarines, which are hard to detect and target—rather than expanding the size of the arsenal itself.

China's first atomic bomb was tested on October 16, 1964, at Lake Lop Nor (Image source: http://www.china.org.cn/english/congress/228244.htm via Wikimedia Commons)

China's first atomic bomb was tested on October 16, 1964, at Lake Lop Nor (Image source: http://www.china.org.cn/english/congress/228244.htm via Wikimedia Commons)

Finally, New Delhi needs to engage in a substantial dialogue with partners in Asia, as well as the US, on what the region’s nuclear future ought look like. Like India, many Asian states face military threats from China, but have so far decided they are secure under the umbrella of nuclear deterrence provided by the US. Japan, notably, is the only non-nuclear weapons state to have significant plutonium stockpiles, as well as the technological capabilities to build them. It has chosen not to, though.

That might well change, should the degree to which the US is willing to commit military resources in Asia diminish. In 1971, General Park Chung-hee’s military dictatorship ordered his scientists to develop a nuclear weapon inside six years, along with long-range missiles. A now-declassified diplomatic cable sent by the United States’ ambassador Philip Habib in 1974 records that the decision was driven by “increasing doubts about (the) durability of US commitments”.

In the Korean war of 1950-1953, the historian David Halberstam has said, People’s Liberation Army troops arrived in an unceasing flow to replace the dead. The US’ citizens, residents of an affluent industrial society, were unwilling to pay the same cost, measured in sons. Like in Vietnam two decades later, the United States won each battle—but proved ultimately incapable of victory.

From Australia to South Korea and Japan, there is renewed debate on how durable America’s commitment to Asian security will prove. It is impossible to judge, yet, how this debate will end—but New Delhi’s own nuclear and strategic decision-making will clearly be contingent on its outcome.

Nuclear weapons are different from all other kinds of weapons: Their use makes the very concepts of victory or defeat irrelevant, holding out the prospect not just of mass-scale death or economic destruction, but the annihilation of entire civilisations. This is precisely why nuclear weapons deter adversaries from considering going to war in the first place. New Delhi must ensure its threat remains credible—while at once recognising that more bombs don’t necessarily mean more security.